Understanding how the design tool known as emotional engagement can make the player enjoy harsh and disempowering experiences

Originally featured on GameDeveloper. This article is only the first part of the study I have recently written about how Reed Hook developers used the player’s emotional engagement on Darkest Dungeon. If the subject seems to catch your eye, I encourage you to read the rest of the article.

Difficulty and disempowerment in a casualized market

With the launch of the new console generation, Sony has decided to make Demon Souls (remake of an original title of the same name made in 2009 for the PS3) one of the most important releases for the PS5. For anyone new or inexperienced player in the medium, the soulslike genre may not be the best decision in terms of accessibility for casual and novice players. Convoluted plot, rough gameplay demanding of reflexes and patience, and many deaths ensured to those who try to progress on an enigmatic world are the main ingredients of Demon Souls, a game globally known for its difficulty. At which moment have the harshness and difficult comprehension of a game turn into unique selling points? What kind of player is attracted to titles with these characteristics?

The number of players has exponentially grown in recent times thanks to the uprising popularity of videogames, so developers have been preparing themselves to create a broad number of experiences enjoyable for the vast majority of players. This phenomenon known as casualization (Sarazin, 2011), has been enhanced due to the increasing division between players and how they choose the difficulty of their experiences. One clear example of this trend is the difficulty options Modern and Retro in the new Crash Bandicoot 4: It’s About Time (Toys for Bob, 2020) (Fig.1), which let players choose between two gameplay configurations: Modern, a more casual approach to the game made for new and casual players; and Retro, which maintains the old life system reminiscent from the arcade era.

Fig 1. The different playstyles available to choose in the last entry of the Crash Bandicoot franchise are one of the latest examples of how games are adapted to different audiences.

When players perceived how the medium was changing towards game experiences more accessible demanded by the masses, they began searching for different approaches to games. Indie games had just recently begun selling on the most important platforms, so new potential buyers got there what they wanted, games not made for the typical player. Titles in which the metaphor or mechanics are usually related to the phenomenon known as disempowerment.

Johan Huizinga, Dutch philosopher and historian, defines disempowering fantasies in his book Homo Ludens (1938) as game fantasies in which, voluntarily, the user has his power restricted in a safe and limited place with the objective of being entertained.

These restrictions are typical components found in a lot of indie and AAA titles. Disempowerment elements are usually seen in horror games, particularly in the Survival Horror genre, though it isn’t exclusive for them. Different videogames acclaimed for the critics such as Death Stranding (Kojima Productions, 2019), Alien Isolation (Sega, 2014), or Darkest Dungeon (Red Hook, 2015) have all in common their try to make the player feel vulnerable or weak against the game world that defies the user. These titles use various design tools in order to create disempowerment, such as having limited survival resources for the player, making him or her see the power disbalance between their avatar and the enemies, or facing harsh situations with bad outcomes.

Many times, game metaphors from these types of titles put the player under pressure in situations where our acts are morally grey, so the outcome of our own decisions falls under our own conscience. For example, Frostpunk (11 Bit Studios, 2018) (Fig.2) is a videogame where the player has to manage a small village in extreme winter conditions, having to choose many times about the disposal of villager’s corpses, child labor, food rationing, medicine, and other resources in order to represent the real cost of surviving in that world.

Fig 2. Frostpunk faces the player with different extreme situations where the survival of the group is more important that the morality of our acts.

The market has adapted to offer this type of experience, and time and the evolution of the market showed us that there is an audience large enough to maintain them. Then, we should ask: What is about these games that make them enjoyable for the player, even if they are defined by design to make us feel bad?

Defining the player : empathy and agency

When we talk about how games are an art form, we defend the interactivity and immersion of these experiences as the defining element that distinguish themselves from other cultural products. Nicole Lazzaro explains in her academic paper Why We Play Games: Four Keys to More Emotion Without Story that the immersion component seen in videogames is created by the moment-to-moment experiences inside them, only when the player comprehends the available actions (mechanics), objectives, capacities and limitations of the title.

It’s here where the role of the videogame designer comes in place, being his duty to search and create the phenomenon known as meaningful play. Defined by David Kirschner y J. Patrick Williams in Measuring Video Game Engagement Through Gameplay Reviews, the research explains how this technic helps the player incarnate their avatar with the most fidelity possible. To help create the desired experience, a game has to offer these 5 components:

- Challenge: knowledge and abilities necessary to accomplish our objectives.

- Control: different stages of decision making and impact over our surroundings.

- Immersion: different grades in which the player is absorbed by the activity.

- Interest: level of desire that the player has in order to do something.

- Motive: perceived value of the activity, which requires effort.

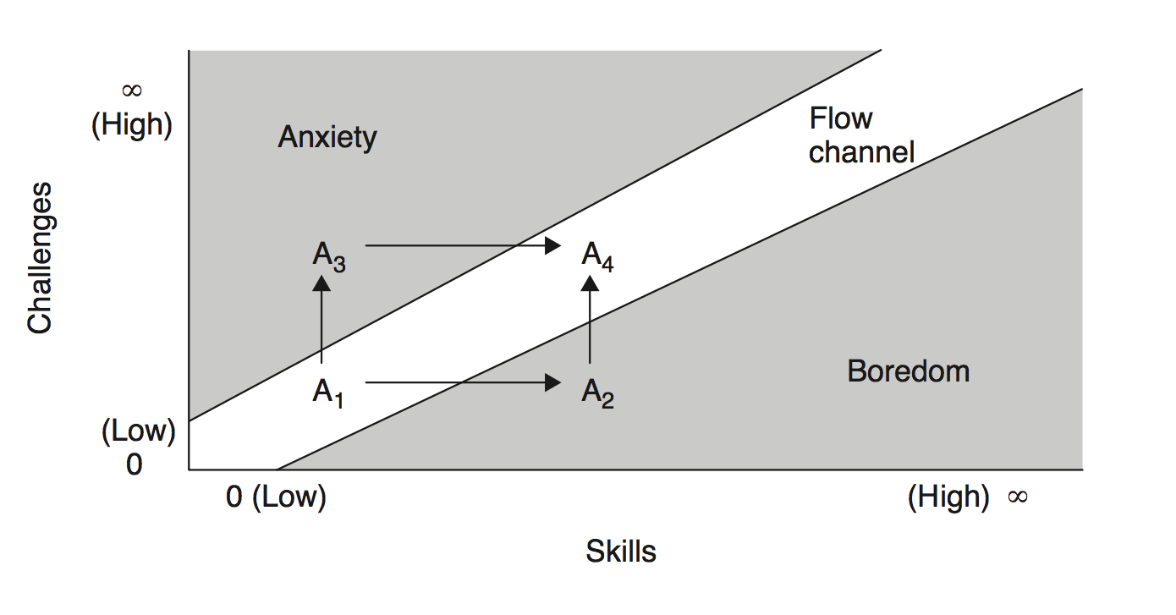

Among these 5 elements, challenge and control are the most important of the list, because those two generate the immersion, interest, and motive in the player. About how challenge works, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi writes his famous flow theory, which not only applies to videogames. Flow is defined as a state of concentration or complete abstraction produced by the activity that is taking place. The most efficient way of creating this effect on the player is by introducing a challenge that grows in difficulty at the same time as the player skills do.

Fig 3. This chart from “Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience” shows how the Flow channel works. If the challenge is much bigger for the player, we will generate anxiety on him/her. But if it is perceived as simple for the user skills, he/her will get bored.

Then, when the connection between player and game is positive, the subject will have the time and motivation needed to understand the remaining game elements, thanks to him/her being fully immersed in the gameplay. When we are in the flow channel, the actions and relations of our avatars feel like if they were real to us. As Harrison Pink says in his GDC 2017 talk called Snap to Character: Building Strong Player Attachment Through Narrative: as the player and his/her avatar progress together and spend time with other characters of the same game world, the user will start to create emotional bonds with them.

Those emotional bonds can’t be imposed on the player, because they require time and adaptation to the game universe, including all the presented characters. Empathy and other emotions that the user may feel can affect how him/she faces different game situations because the human factor can make us act differently towards situations where our friends/foes are involved. This phenomenon is called Emotional Inertia, and it is one of the most valuable signs that show a high level of immersion.

At the same time, a player that feels empathy for the other characters trigger’s that all our actions regarding their future or wellness are transformed into moral decisions, due to the moral implications that they have on the user. We feel then that our actions and abilities have consequences that can influence the game world and plot, creating the sense of agency.

Making an impact in a fictitious world

Player Agency is defined by Karen and Simon Tanenbaum in their paper Commitment to Meaning: A Reframing of Agency in Games as the satisfactory sensation of being able to take important decisions and see the results of their actions.

As commented before, immersion through the use of player emotions is a clear example of how significant this experience is for him/her, so emotional inertia is a phenomenon that designers look forward to. In order to improve those emotional bindings, we know that players need an adaption time, but as Meg Jayanath explains in her GDC 2016 talk Forget Protagonists: Writing NPCs with Agency for 80 Days and Beyond, empathy flourishes in the player not only when the characters have the same objectives as we do, but when they show human traits that makes them feel real. That is accomplished by letting us share moments with them, where we see how these characters are affected by the positive and negative parts of the adventure, remarking the bad side of it. That’s because the effort and loss suffered from those characters make us see them as our true companions.

Immersion, agency, and empathy are fundamental components for the design tool responsible for this behavior, known as emotional engagement, defined by Kiel Mark Gilleade and Jen Allanson in their academic paper Affective Videogames and Modes of Affective Gaming: Assist Me, Challenge Me, Emote Me (2005) as using player emotions as an element that is going to influence his/her actions.

A clear example of the use of this design tool can be seen in titles that build their gameplay and progress around how the player connects with characters from the game world, who will help us progress and upgrade our town. Those kinds of games offer almost complete freedom to the player. Animal crossing: New horizons (Nintendo, 2020), The Sims (Maxis, 2000) or Stardew Valley (Eric Barone, 2016) are examples that have the mentioned characteristics in which the objectives in our gameplay are influenced by the relations with other characters (Fig.4).

Fig 4. In Animal crossing: New Horizons, our relations with our neighbours will be upgraded if we accomplish some missions or tasks for them, such as bringing them gifts based on their likes, asking them about their day, or bringing them their lost objects.

So, when a videogame fulfills all the basic requisites (challenge, control, immersion, interest, and motive) needed for it to create a significant experience in the player, they will be more inclined to generate emotional bonds with the game world and their characters. Then, designers use that emotional engagement created in the users to create significative experiences that resonates with them.

We know that the affective gaming toolset usually works in a positive context where players want their companions to be happy and accomplish their missions, while their enemies suffer and fail. But… What about if our friendly characters attack each other? And if our enemies always have an advantage? What is the main motive behind those design decisions that provoke situations where the player doesn’t have any positive outcomes?

Painful art and disempowering fantasies

According to the work of the designer Valentina Tamer in her book Fantasies of Disempowerment: The Lure and Value of Voluntary Power Loss in Single-Player Video Games (Bhatty, 2016), she says that in-game context, disempowerment is the voluntary restriction of the player with the objective of entertainment or other psychological gains. This phenomenon isn’t exclusive to videogames, and can be seen in other entertainment activities such as horror films, thematic fun rides, escape rooms, or sexual activities such as BDSM (Bondage, Domination, Sadism and Masochism)

Disempowering experiences aim to make the player understand, through suffering or pain that afflicts our avatars, the effort and price needed to live or progress on those worlds. For example, Hideo Kojima designs for Death Stranding (Kojima Productions, 2019) an experience in which the players relieves the isolation of a decimated world through the eyes of a lonely carrier in his way to connect the remaining human civilization while delivering packages. In Pathologic 2 (Ice-Pick Lodge, 2019) (Fig. 5), the developers challenge the player with limited time for him/her to save few people from the Black Death, knowing from the beginning that you are not going to be able to cure everyone.

Fig 5. With only 12 days of real time, in Pathologic 2 the player incarnates the only doctor in a town destinated to be destroyed by a near war and the Black Death. It’s in your hands who are you going to cure and which methods are you going to use, because usually saving a life means ending others.

These types of fantasies are now more common, thanks to both the market growth and the audience's search for new and exciting experiences. Those have allowed developers from around the world to design titles with metaphors not aimed at the general public, that usually talk about rough situations or interesting ideas that add a lot of value to the video game medium.

Value of the experience

In order to understand the motives behind this desire within the players to feel vulnerable or powerless, Valentina Tamer in her book Fantasies of Disempowerment: The Lure and Value of Voluntary Power Loss in Single-Player Video Games (Bhatty, 2016) explain how these experiences fall into the artistic category known as Painful Art. According to Tamer, we define Painful Art as those artistic works that generate pleasure and pain in the user.

There are several theories regarding why we enjoy this phenomenon:

- Control theory: users are able to endure content that is not pleasant in disempowering experiences because we are aware of having control over them, so they can be finished whenever we want.

- Compensation theory: our human mind allows itself to feel negative emotions if it knows that they can be followed by positive emotions. That catharsis is the compensation that we humans want from the experience. Furthermore, Painful Art is a crucial element for maintaining a healthy emotional state in a balanced mind.

- Conversion theory: the experience isn’t only of pain, Unpleasant sensations turn into pleasant ones thanks to the influence of other motivations more prominent.

- Rich experience theory: the idea of the susceptibility towards boredom can be produced by craving emotions. Based on the scientific investigation of the philosopher René Dubos, he explains that people tend to prefer experiences that produce emotions rather than feeling boredom, even if it means enduring pain.

- Mood control theory: all users use different kinds of methods in order to influence and change their mood. This concept explains why people enjoy comedy to raise their spirits or listen to sad music to collect in pain.

- Meta experience theory: people can feel various emotions at the same time, including emotions towards our own emotions (meta-emotions). Feelings of fear, empathy, loss, or concern make us feel human, and Painful Art is a simple answer that can make us react to those situations.

- Power Theory: control doesn’t influence the emotional impact of the experience, rather is the main attraction of the activity. Players enjoy seeing and testing how much pain are they able to endure, which brings them feelings of power, strength, and pride.

Painful Art creates a rich experience full of emotions to fight against boredom, but it can be also used to control our own mood. The meta-response of the audience towards these artworks and feelings produced are answered with feelings of curiosity, satisfaction and pride.

All these theories can be merged between them as motives to test this kind of experience, but there isn’t for sure an exact motive about why we as humans search for these fantasies in our entertainment. This is because not all people enjoy horror or tragedy stories in the same way.

Disempowering elements

Due to the described disempowering experiences, and also though the fact that we can’t help making a subjective interpretation of the game comparing the previous experiences the player has met, we question our powers and abilities.

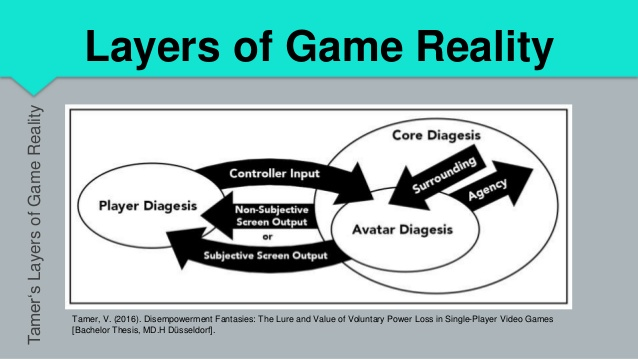

To better understand how disempowerment works, we should know about the 3 basic layers of the Game reality, for which information flows and is transmitted between the user and the videogame. (Fig.6) Valentina Tamer defines 3 different layers:

- Game World (core diagesis): the interactive space of the game, with its limits and mechanics, that let us interact with the world.

- Avatar (avatar diagesis): the perception of our own avatar.

- Player (player diagesis): the perception of the player, with the controls and inputs that let us incarnate the avatar.

Fig 6. Scheme of the 3 layers of Game Reality and how they relate. Valentina Tamer 2016

When the communication between all those different layers change, distort or is restricted, we generate in the player feelings of disempowerment. According to Tamer’s investigation, changes in mechanics or other game elements that create this phenomenon are:

- Audio-visual distortions and restrictions, in which the perception of our avatar is distorted, and this is reflected in how the game shows it. Generally, we see those shifts because our avatar has suffered neurological, physical, or supernatural changes (wounds, drugs, sanity loss…). Through these modifications on the core diegesis, the player relieves the distorted reality of our avatar. An example of this phenomenon is easy to see in games that change camera perspective for a fixed position, such as the one in Resident Evil (Capcom, 1996) which not only gives ambiance but also restricts very well what the player can see and whatnot.

- Spatial distortions and restrictions are those modifications in which the Game World generates changes in the interaction of mechanics and abilities between the game and the player. Within the same type of distortions, spatial restrictions take away the avatar’s freedom to move through the place. In Silent Hill 2 (Konami, 2001) the place which the player explores is constantly changing its limits and available roads in order to make us lose ourselves in the town.

- Restricted resources, managed by designers that intent to limit the available important items, to hindering the player progress. Those resources can be vital components for our character, such as health or stamina, or other objects such as ammo or tools. In Word of Horror (Paweł Koźmiński, 2019) the player has to worry not to let his/her avatar health and sanity doesn’t drop below 0, but trying to restore any of those values is very hard because items or actions that help us are rare.

- Power imbalance between our avatar and our enemies gives our playable character a clear disadvantage, which increases the perceived challenge. Those encounters distinguish themselves from having stronger foes, invulnerable, or in more numbers. In some titles, our avatar can’t escape from his death, due to having reached the end of the adventure or cause the game wants to let the player see what is beyond death. For example, in Bloodborne (From Software, 2016), when the user gets control of his/her avatar for the first time, because we don’t have any weapons, the first enemy is going to kill us for sure. This will send us to the dream of the hunter, the central HUB of the game, and a safe place for our avatar to level up and buy things.

- Incomplete narrative or wrong information, which creates disempowerment in the user because the lack of knowledge makes us harder to get a grasp of what are we doing or what are we going to face. Related to this category, avatars that don’t have any impact on the plot of the game world make us feel helpless. In Doki Doki Literature Club (Team Salvato, 2017), our avatar can’t avoid the suicide of one of the main characters, even though we can foresee it and try to help.

- Moral decisions put the player in a place where he/her has to endure and acknowledge the weight of the possible outcomes for their actions, with the influence that they may have in other characters, plot, or the game world. Even though normally choosing our own path is something empowering, it is the reverse when we create the feeling of guilt towards our behavior. In The Walking Dead (Tell Tale, 2012), our avatar Lee is the leader of a group of survivors, represented as complex human beings whose fate will depend on our actions.

Enjoying pain

In order to understand the reason behind why we enjoy these experiences, continuing with the work of Valentina Tamer in her book Fantasies of Disempowerment: The Lure and Value of Voluntary Power Loss in Single-Player Video Games (2016) she explains different motives for this. It is important to say that, even if all these theories can’t apply to all players and videogames, they can lean on each other and give perspective about what do we see on those titles. These are:

- Rich experience theory: starting with the investigation of Smuts in his paper Art and Negative Affect (2009), where he explains how art can generate valuable experiences for the player that gets him/her out of boredom, we can extrapolate the same effect on videogames. This theory proposes that disempowerment brings more value to the general experience, so much so that it requires more effort from the player, making the perceived challenge feel higher, and its reward sweeter

- Thrill theory: studying the book from Apter & Kerr Adult Play (Garland Science, 1991), they present the Reversal Theory, which explains how we humans search for experiences that generate in us physical and emotional reactions (increased pulse, adrenaline…). Usually, those reactions are born when there is a real danger in those actions, but videogames let us experience those feelings in a secure environment.

- Underdog theory: Tamer explains how disempowering in videogames is often perceived as something attractive for the player because it lets the player face difficult situations where he/her is the underdog, in a way that the effort needed to overcome those challenges produces personal recognition for them. This theory is strongly grounded in the phenomenon known as justification, defined by Klein, Bhatt y Zentall in the paper Contrast and the justification of effort. (2005). Here they explain that the more effort put by the user in overcoming an obstacle, the more important and significant will the victory be seen by the player.

- Regression theory: in psychoanalysis studies, Freud defines Regression as a defense mechanism that lets the player go back to a more childish status, where they didn’t have any responsibilities or the necessity to be seen as adults. This makes videogames work as an anti-stressant, thanks to permitting the player fail without any bad consequences. Regression can produce in us a pleasant sensation as it liberates us from the continuous pression of trying to have always control over all situations.

- Reframing theory: following the investigation of Tamer, it explains that disempowering in videogames forces players to search for creative solutions to those hard challenges, which makes them aware of other perspectives regarding their context and objective. According to Csikszentmihalyi: the more severe the restriction, the more creativity, and determination will be required.

Now that you know about how emotional engagement functions and why there are players craving for disempowering fantasies, I encourage you to read my full analysis about how Darkest Dungeon uses these tools in its favor to convey through gameplay a great history with a very harsh meaning. It will be finished and posted before the final release of Darkest Dungeon 2.